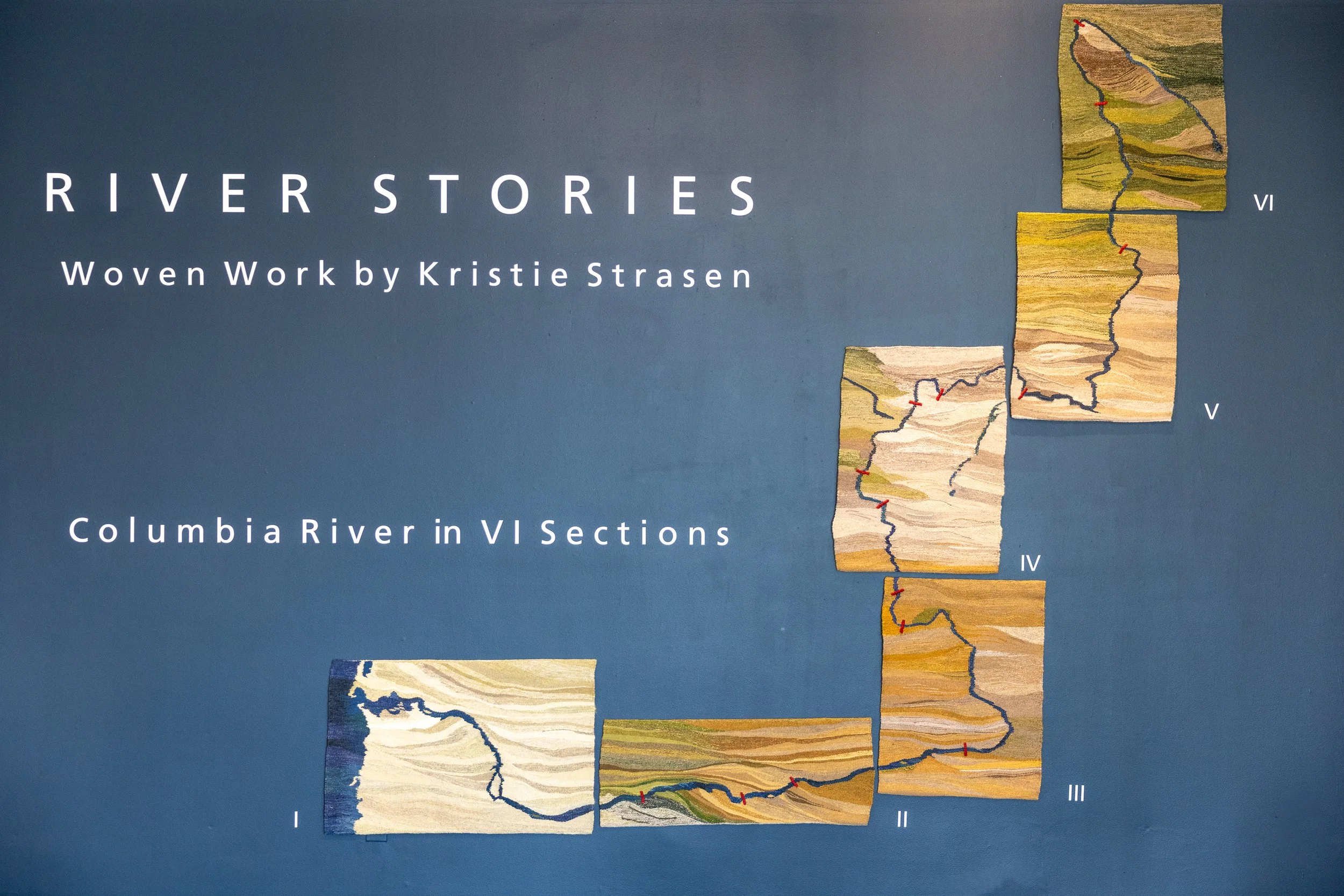

R I V E R S T O R I E S

Woven Work by Kristie Strasen

Columbia Gorge Museum | June 1, 2025 - August 31, 2025

“River Stories” is a series of handwoven tapestries depicting the Columbia River and selected tributaries that feed into it as it passes through the Columbia River Gorge. The tapestries create a visual narrative that touches on the geological, cultural, and political history of these rivers and their critical role in Native American sovereignty, fishing rights, land management, irrigation, and environmental balance.

_________________________________________________

Ten thousand years before Manifest Destiny, the land along the rivers of the Columbia was home to a thriving Indigenous population whose spiritual beliefs and cultural practices included respect for the land, the rivers, and the salmon who swam in them.

In fewer than two hundred years, Western Expansion has profoundly altered this landscape. The rivers and the fish in them have had to find new ways to survive, and the Native people who lived in these areas for thousands of years have had to find new ways to be.

_________________________________

On June 18, 2024, the U. S. Department of Interior issued a “Tribal Circumstances Analysis” which documented, in detail, the historic, ongoing, and cumulative impact of Columbia River dams on Columbia River Basin Tribes. The report is a first step in acknowledging the damage done and exploring ways to mitigate the harm caused.

Columbia River in VI Sections

“The Columbia River in VI Sections” is woven in six separate segments and maps out the entire length of the Columbia from its headwaters in British Columbia to its terminus in the Pacific. The fourteen dams that interrupt the natural flow of the main stem of the river are prominently called out with red bars.

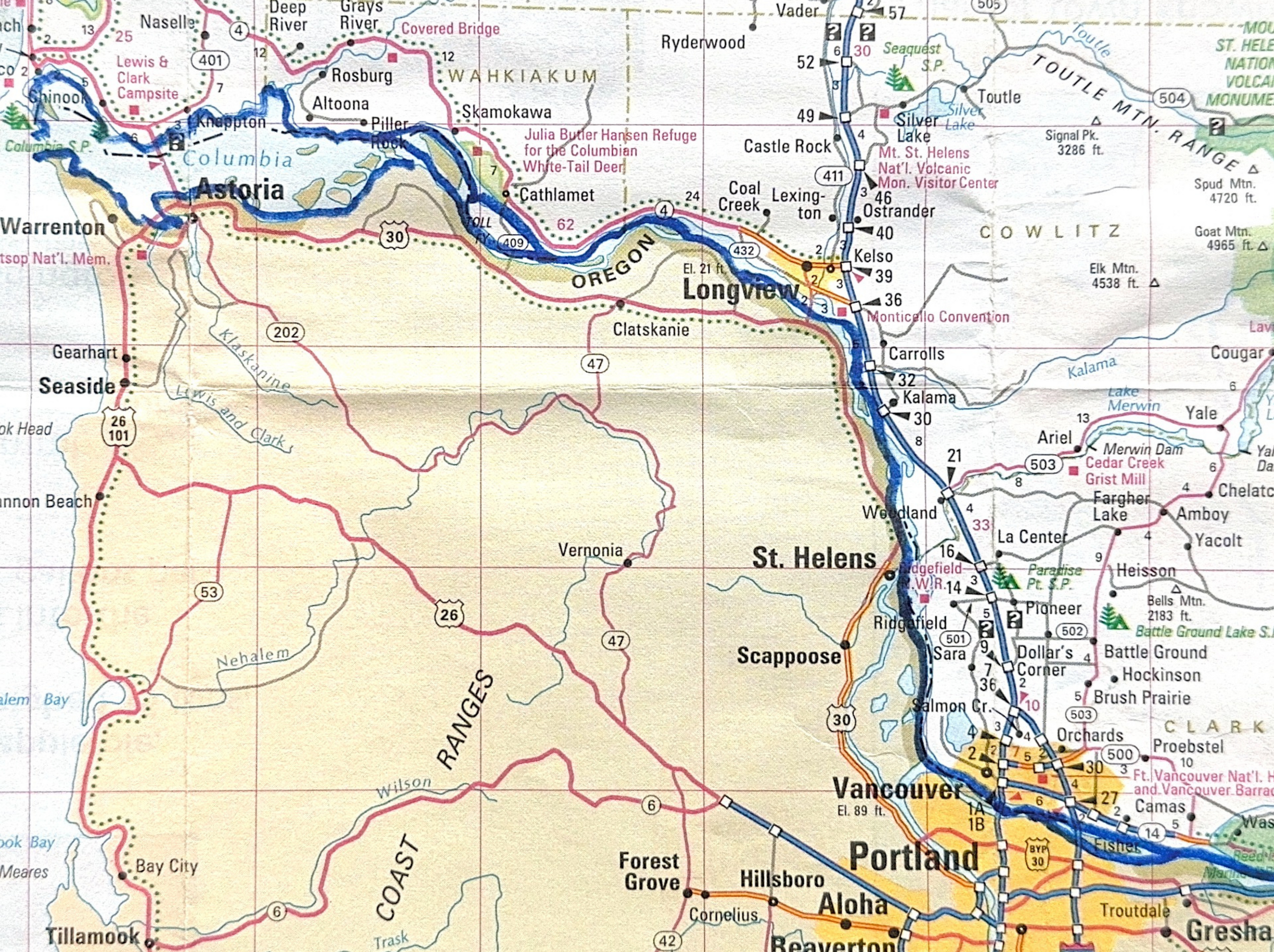

Section I - Mouth of the Columbia River

After travelling over 1200 miles, the Columbia River terminates in the Pacific Ocean. The exceptionally steep drop of the river, from its origin in the Canadian Rockies to its terminus in the Pacific, accounts for its astonishing muscle. It moves with such force that it shoots a four-hundred-mile finger of fresh water out into the sea. The mouth of the river is notoriously dangerous, and many boats and ships have met their demise attempting to access the Columbia.

Thanks to the Missoula Floods, the landscape at the mouth of the river is relatively flat with exceptionally fertile soil. The dense forest of the Cascade Mountain Range transitions to a gentle landscape smoothed by thousands of years of repeated flooding.

There are no dams in this section of the river. It has been allowed to follow its own course, swinging due north for a while before it turns west and heads to the Pacific.

Section II - Columbia River Gorge

Dams (West to East)

1. Bonneville 1938

2. The Dalles 1957

3. John Day 1971

The Columbia River Gorge offers a unique landscape that owes its formation to the Missoula Floods occurring at the end of the last Ice Age (13,000 - 15,000 years ago). The Columbia River is the only river from the Arctic to South America that breaches a major mountain range and makes its way to the Pacific.

This section of the Columbia has three significant dams: Bonneville – completed in 1938; The Dalles – completed in 1957; John Day – completed in 1971. All three of these dams were built to generate hydro power, offer flood control, and bring irrigation to the dry desert region east of the Cascade Range. Although all three dams have fish ladders, the reservoir behind John Day forms the deadliest stretch in the entire river for migrating salmon due to its 76-mile-long length.

These dams flooded ancient Native villages, in continual use for over 10,000 years, submerged sacred fishing sites, flooded ancestral burial grounds, and “disappeared” Celilo Falls.

Section III - Hanford Reach

Dams (South to North)

1. McNary 1954

2. Priest Rapids 1961

3. Wanapum 1963

This section of the river is where the Hanford Nuclear Works was built in 1943 as part of The Manhattan Project. The mission was to produce plutonium for the atomic bomb, and the project employed over 50,000 people. This site was considered ideal because it was “out in the middle of nowhere,” and it was adjacent to a cold, rapidly flowing river.

While this area may have appeared to be exceptionally isolated from human settlement, it was still the traditional homeland for Native tribes as well as a handful of White settlers. People were given thirty days to vacate the land. White settlers received some compensation from the government, but the Natives did not.

The three dams in this section of the river had an equally detrimental effect on the lives of the Natives whose land, sacred fishing sites and burial grounds were submerged. Priest Rapids Dam was named after a nine-mile stretch of rapids that was subsequently flooded out of existence. There are no Rapids at Priest Rapids Dam.

Section IV - Columbia Basin Irrigation Project

Dams (South to North)

1. Rock Island 1933

2. Rocky Reach 1956

3. Wells 1967

4. Chief Joseph 1955

The main purpose of the four dams in this section of the river was to generate hydropower. The Rock Island Dam was the first to be completed on the main stem of the Columbia in 1933.

Chief Joseph Dam, named in honor of the famous Nez Perce chief, is the biggest dam owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It is also the second-largest hydro-producing dam in the U.S. Chief Joseph does not have a fish ladder.

The construction of the four dams in this section had a significantly negative impact on Native tribes who had lived here for thousands of years. They suffered displacement from their ancestral lands, complete disruption of traditional fishing locations, and loss of sacred sites, including burial grounds. Ancient petroglyphs were forever submerged under the new course of the river.

Section V - Grand Coulee

Dams (South to North)

1. Grand Coulee 1933

2. Keenleyside (BC) 1968

The construction of Grand Coulee Dam is an epic story for an epic dam. When Franklin Roosevelt observed the Columbia River during his vice-presidential campaign in 1920, he recognized its potential for generating power. Roosevelt’s grand vision for bringing water to the arid region of the Columbia became a reality with the building of Grand Coulee Dam.

Grand Coulee Dam was built as the country emerged from the Great Depression. Work on the dam single-handedly employed thousands of workers. The Columbia Basin Irrigation Project made arable land out of the dry desert and provided an incredible opportunity for anyone willing to move to this isolated corner of the country.

What Grand Coulee Dam did not do was consider the catastrophic effect it would have on salmon migration and the Native population who called this land home. This dam – which was a phenomenal feat of engineering and a manifestation of “the American Dream” – was also the harbinger of ecological disaster, in part, because it was not designed with a fish ladder. The dam fully submerged Kettle Falls, a fishing site that had existed for thousands of years, and obstructed the river, preventing any salmon migration.

The dotted lines in Section V mark the American-Canadian border. Keenleyside Dam is discussed in Section VI.

Section VI - Columbia River Headwaters

Dams (North to South)

1. Mica 1973

2. Revelstoke 1984

3. Keenleyside 1968 (Section V)

The Columbia River originates in the southeast corner of British Columbia between the Canadian Rockies and the Selkirk Mountains. The river flows northwest for almost two hundred miles before making a sharp hook south and flows more than one thousand miles to its terminus in the Pacific Ocean. The river begins its journey at 2650 feet above sea level and flows with great force. The Columbia River is the largest river by volume flowing into the Pacific Ocean, anywhere along the 9600-mile coastline from the Arctic to South America.

Two of the three dams in British Columbia have fish ladders (Mica and Keenleyside), while Revelstoke does not. The Canadian dams flooded the Native homeland and that of White settlers. The dams submerged fertile valleys and old-growth forests, killed wildlife, and forced First Nations people from their traditional lands.

The Canadian dams are part of a sixty-year-old treaty with the United States and is being renegotiated.

Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area

This two-section tapestry provides a visual narrative of the land in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. This designated area begins about seventeen miles from Portland and extends for eighty-five miles through the verdant Cascade Range into the dry desert region beyond The Dalles.

The federal designation for the Gorge as a “national scenic area” was established in 1986 through the devoted efforts of John B. Yeon, a successful Portland businessman, and Nancy Russell whom Yeon recruited to help with the effort to get local and congressional support. The Columbia River Gorge is the largest of all the designated scenic areas in the country and is the most well-known.

Acquiring the land that became the Gorge Scenic Area took tenacity, patience, money, and excellent sales skills. Nancy Russell is credited with making it happen. There was plenty of opposition from those who saw this designation as a hindrance to development – which frankly was the intention. But even those who initially opposed the idea eventually came to see the Scenic Area designation as a shield to protect and enhance the unique landscape we all love.

Ronald Reagan signed the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act – one of the few pieces of environmental legislation he signed in his eight years in office.

Lower Klickitat River

The Klickitat River originates on Mt. Adams and flows generally south to its convergence with the Columbia at the town of Lyle. While the river is ninety-six miles long, the last 10.8 miles have the national designation of a “Wild & Scenic” river and are thus protected from development along its banks.

Native Americans lived all along the Klickitat long before European settlers and were skilled horsemen, hunters, traders, and fisherman. This area was also known for the intricate baskets Native women produced as utilitarian vessels for everyday life.

The Klickitat River was never dammed and fish ladders incorporated into the design of the Bonneville Dam (downstream from the mouth of the Klickitat) allowed the salmon who managed to navigate through the ladders, to reach their spawning grounds on the Klickitat River.

To this day, it is possible to see Native fishermen dip netting for salmon by standing on scaffolding built out over the river. The Lower Klickitat River tapestry celebrates the complex path the river takes through the narrow basalt canyons it has etched over thousands of years.

Little White Salmon River

The Little White Salmon is a pristine and relatively untouched river that offers plenty of white water and stunning waterfalls - the most significant being Spirit Falls with a 33-foot drop.

Originating in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, the Little White Salmon is considered one of the best Class V rivers in the country. It flows through rugged terrain to Drano Lake and the Columbia River and is a favorite among experienced kayakers. (Emphasis on experienced). The river flows with such force that it can be used year-round, but it is a highly challenging river along its entire length.

The Little White Salmon was a revered location for Native Americans before colonization. There were settlements near its banks, and a large encampment of Natives made their homes at the mouth of the river at Drano Lake in the summer.

The name “Drano” comes from a Frenchman named William Drano (known as French Billy) who settled in the area in the 1800s and built a flume across his homestead and down to the river. To this day, Drano Lake is a favorite location for fishing.

The Little White Salmon tapestry presents the path of the river through verdant forest and honors Spirit Falls.

The White Salmon River

The White Salmon River has special significance for our region. For millennia, Native Americans lived along the river and sustained their existence from the abundant salmon the river provided. Native camps moved with the seasons but were present year-round.

In 1913 Condit Dam was built a little more than three miles up the river to generate hydropower. Unfortunately, Condit Dam did not take into consideration the salmon population and did not include a fish ladder in its design. The dam made it impossible for salmon to reach their spawning grounds north of the dam. The fact that salmon were unable to return to their spawning grounds quickly decimated the salmon population on the White Salmon River.

After nearly one hundred years, the dam was removed in 2011. This was a significant event and had a dramatic effect on the health and well-being of the river. The salmon quickly returned, and the river, now clear of dams, runs freely from its headwaters on Mt. Adams to where it converges with the Columbia, just west of the town of White Salmon. The river is now a popular destination for white water kayaking, canoeing, and rafting. And it is a popular place to fish for salmon and trout.

This two-piece tapestry of the White Salmon River celebrates the simple beauty of the river’s free-flowing path to the Columbia.

Tributaries

The Columbia River has over sixty tributaries – both large and small. The Snake River, which has a story of its own, is the largest tributary to the Columbia. The Snake is over one thousand miles long and before it was dammed, produced over 40% of the salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River Basin. The dams have made barge navigation possible to Lewiston, Idaho, making it the most inland seaport on the West Coast. The dams have also brought the salmon population on the Snake River to near extinction.

Small creeks and streams like Catherine Creek near Lyle also contribute to the tremendous volume of the Columbia.

Many of these tributaries play a vital role in salmon migration and spawning and are of key importance to the overall health of the Columbia River and salmon in particular.

This series of small tapestries pays homage to all the Tributaries to the Columbia River.

Tribute to Waterfalls

The Pacific Northwest boasts the highest concentration of waterfalls anywhere in the U.S. More than seventy-five of these are scattered along the Columbia River, particularly in the Gorge.

The dams constructed on the Columbia River have flooded two significant waterfalls: Kettle Falls was “disappeared” with the building of Grand Coulee Dam. Celilo Falls was completely covered by back water from The Dalles Dam. In both cases, the building of these dams destroyed highly significant Native fishing sites and wreaked havoc on salmon migration.

Kettle Falls had immense cultural and economic significance to Natives. It was a vital fishing ground as well as a center for trade and a place for ceremonial and social gatherings. Native Americans considered the land around Kettle Falls sacred. Many Native burial grounds were flooded with the building of Grand Coulee.

The site of Celilo Falls marked a Native American trade route that was actively used for over 10,000 years. The area around the falls was a major fishing site, a trading hub, and a place of spiritual ceremonies.

A Tribute to Waterfalls honors these lost waterfalls as well as the waterfalls that still exist.

Chinook

It would be difficult to overstate the tremendous importance of salmon to the local economy and particularly to Native Americans.

For Natives, salmon are a symbol of renewal, prosperity, and connection to the natural environment. Tribal cultures are deeply entwined with salmon and view them as a sacred resource. Salmon are considered an indicator species, meaning their health and abundance is directly linked to the health and well-being of our entire ecosystem.

Salmon were the primary food source for Natives for millennia. They served as a kind of currency and the Native Americans who controlled salmon resources were considered wealthy to tribes who came to trade.

In modern times, salmon have become an important source of livelihood for commercial fishermen who have supported themselves by fishing for salmon.

The dams built without fish ladders on the Columbia River had a catastrophic effect on the salmon population. This translated to a catastrophic effect on the Native communities who depended on salmon as their primary food source and means of survival.

It is impossible to tell a story about rivers in the Pacific Northwest without considering the importance of salmon.

Chinook symbolizes all salmon that depend upon the river for their survival.